Our Medical Advisors, Dr David Milecki and Professor Paul Van Buynder, have explained the current COVID-19 tests and how to interpret their results.

COVID-19 Tests

There are two types of tests “available” for detecting SARS-CoV-19, the virus responsible for COVID-19 disease.

Nucleic Acid Tests

These tests look for the actual virus in the body usually from respiratory tract specimens such as a nose swab.

The tests usually identify either two or three components of the genetic material (RNA) within the virus. This RNA is usually identifiable in respiratory samples in the acute phase of infection. Positive results imply the virus is present and with the clinical picture can aid management of ill patients.

The nucleic acid tests developed for SARS-CoV-19 look at parts of the coronavirus that are unique to SARS-CoV-19 so infection with other coronaviruses such as the common cold will not interfere with them.

Negative results do not fully exclude the presence of SARS-CoV-19 and should be repeated if clinical observations, patient history and epidemiological information suggests COVID-19. It may be too early in the infection for the test to be positive.

These tests require complex expensive equipment and access to testing standards and samples. They are only available in major laboratories but are the basis of the COVID-19 response at the moment.

Antibody Tests

After a COVID-19 infection the body will make antibodies to the virus and a number of groups are looking at ways to detect these antibodies in the blood. They are not useful in the early stages of illness as they take time to develop after you are already sick.

These tests will become important to determine whether you have had the disease before, whether you are potentially immune to the disease and how long you are immune after an infection. They are also critical in seeing whether possible vaccines produce a protective result.

They have some advantages in that they will detect antibodies even if a patient has recovered where the nucleic acid tests are only positive while you are sick.

They have some advantages in that they will detect antibodies even if a patient has recovered where the nucleic acid tests are only positive while you are sick.

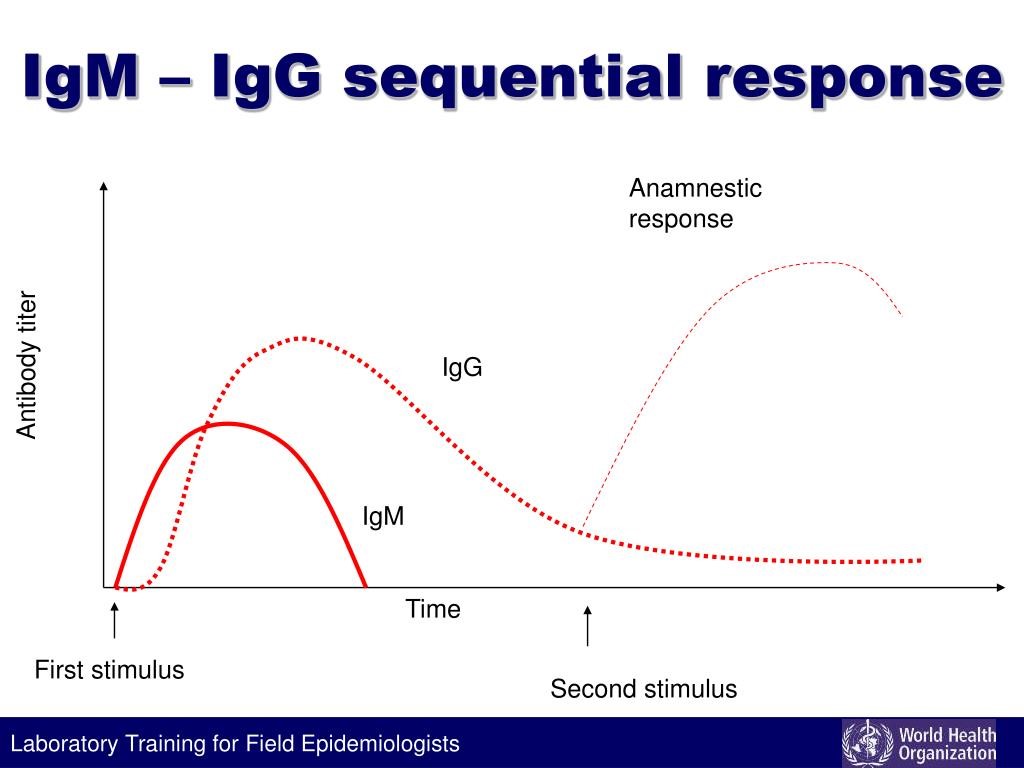

There are a number of antibody classes that are produced. Some antibody types such as IgM appear earlier than others while others such as IgG are more long lasting. Antibodies typically take about a week to develop after exposure to SARS-CoV-19, so if a test is positive it is likely that symptoms have already developed and the person who is developing the illness has had several days to spread the virus. COVID-19 is thought to be infectious in the 24 hours BEFORE symptom onset.

See the graph below as a typical depiction of antibody response over time. IgG is a test for immunity and infection that typically takes at least a couple of months to be detectable and is long-lasting (months to years).

A number of highly sophisticated laboratories have worked on developing these tests since the start of the outbreak with Singapore and China reporting test development early on. In addition Stanford University and some other American sites now have tests that are under investigation.

The tests are being compared to blood samples from people known to have the disease to see at what times they are positive and what the results may mean.

Not all antibodies are protective. Those that are protective are called neutrolising antibodies. If the tests demonstrate these antibodies then the person is protected but we still don’t know for how long. We hope it is for years!

If the antibody test finds other non-neutrolising antibodies then the person may not be protected despite a positive result. A lot more work is required in the coming months in this area.

Recently several 15-minute rapid result self-tests were approved by the TGA. These tests are assays of blood levels of antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 performed by finger pricking a sample. They are being marketed as a test of rapid detection of infection. They are being offered to large companies and corporations, which, in itself is a clue, since if they were the magic answer, the medical profession would not need the involvement of companies.

These tests require more evaluation and I can see a situation where people will be incorrectly reassured by a negative result (a false negative – when they have caught the virus), they relax their guard and then spread the virus to friends, family and workmates, all before the test shows up as positive. Clients are advised not to be part of the chain that leads to such potential outcomes.

Antibody tests certainly do have their place as a valid test for medical practitioners. The tests give rapid results, however, they are not a good way to test for acute infection or for the potential to infect others. It is our opinion that the further development of testing and the use of tests is best left to the medical profession until their role is fully evaluated.

Clients should not play a part in making things worse and taking on some legal risk by promoting methods that lead to negative outcomes including the death of staff or their families.